LRCCS Spotlight: Chen Qinghai

The original version of this post was first published in Chinese. We interviewed Prof. Qinghai Chen, the former Director of the Chinese Language Program who retired in 2013. During this interview, Chen Laoshi shared many of his life stories and experiences from China to the States.

Prof. Chen received his specialized training in Theater and Drama, 1961

LRCCS: Chen Laoshi, we’d love to hear your story; where would you like to start?

Chen Laoshi: I want to start with my childhood in China, which wasn’t easy. My father was a so-called capitalist, so he was a target of the communist movement after 1949. For a long period of time, kids like us had restricted opportunities no matter what we did.

LRCCS: I see. When were you born?

Chen Laoshi: I was born in 1943. After 1949, all kinds of political movements were launched.

Families like mine suffered. Our suffering went on and on, and peaked after the strike of the Cultural Revolution.

LRCCS: Would you care to elaborate?

Chen Laoshi: I remember in August of 1966 when Red Guards came to raid my home. This happened twice. During the second time, Red Guards took a lot of our possessions, many of which were in fact daily necessities, out to the street, and asked my youngest, elementary-aged brother to set them on fire. The fire was huge and even burned the road. Cars in the streets couldn’t drive through and had to detour. They then gathered and sealed the rest of our stuff in a few rooms, and wouldn’t let us use them. Since then, my family had to live on the support and assistance from relatives and friends for many years.

My oldest younger sister and I were about to graduate from college. Our job assignments came through during the Cultural Revolution. During that time, you had to take whatever that the government had offered. You had to go. If you didn’t go, you wouldn’t have a job. I was assigned to Jiangxi Province in 1968. I went to the most impoverished county in the Shangrao Prefecture, and was reassigned to a middle school in a small town. (Note: In China’s system, middle school equals grades 7-12 in the U.S.).

LRCCS: Were you a teacher there?

Chen Laoshi: I was a teacher by title. But actually, at first I wasn’t even teaching. Two factions met and fought every day, and I couldn’t even understand their dialect. About a month later, Jiangxi had all middle schools in the province suspended. Every county would only administer a branch Communist Labor University, but had no middle schools anymore. What happened to teachers? We all got transferred to rural people’s communes for “re-education” in terms of physical labor. So I started working with peasants in the padded rice field every day.

About half a year later, every commune had to restart a small middle school, and needed teachers again. So I was “borrowed” by the local commune as a temporary teacher. This happened in the fall of 1969.

Chen Laoshi was living in a remote area in Jiangxi Province for re-education, 1969

LRCCS: What did you study when you were in college?

Chen Laoshi: I studied English. But it was really tough to learn English back then. We couldn’t access any foreign materials, nor did we have native-speaking teachers. The school informed us that we were not allowed to speak English with any foreigners that we saw in the street. You would be responsible for all possible consequences if you disobeyed. As a matter of fact, the Cultural Revolution started while we were studying, so we didn’t even get to finish.

Going back to my experience in Jiangxi, I got back to a school and started teaching in its real sense. However, English was not offered for political reasons, so they had me teach Chinese. We had no textbooks, nothing at all. All I could do was get materials from newspapers. It wasn’t until 1972-73 that people like me got the official teacher’s title back.

My students from back then still remember me to this day, over 40 years after. About 6 years ago, they found my on the Internet and wrote me an e-mail. They invited me to revisit the town. In 2012, my wife and I finally made the trip. Many years have passed, and that place has totally changed. Of course, only one thing remains unchanged, and that is the feelings between my students and me. My students told me that in a remote place like that, there could not have been a teacher like me. I seemed to have opened a door for them, a door that lead to the outside world.

LRCCS: Was your wife in Jiangxi during that time too?

Chen Laoshi: No. She was in Hangzhou as a faculty member in Zhejiang University. Later, it took us an enormous effort to achieve my transfer from Jiangxi to Hangzhou. I worked at the Middle School Affiliated to Zhejiang University. We soon had our only child.

LRCCS: When did you transfer to Hangzhou?

Chen Laoshi: It was 1975.

The Cultural Revolution ended soon after that, and universities had resumed their admission. During that period, the students at our school studied so hard, and studied so well. I also tried my best to help them. My efforts soon paid off. My students did impressively well in every year’s College Entrance Examination. My teaching was videotaped and broadcasted nationwide through the Education Channel of China’s Central Television. I also had publications about English education. So I became one of the best teachers in Zhejiang Province. During that time, my classes were observed by teachers from different parts of the country who came to learn in Hangzhou for professional development

In 1984, the Municipal Government of Hangzhou appointed me Vice President at the Hangzhou College of Education, an institution for the training of middle school teachers. I was in charge of academic and student affairs, and also taught classes from time to time. I was very hopeful about the Chinese “Reform and Opening” back then, and I felt that I should contribute my bit to the country. But soon I found out what was really happening in the government, and I became very disappointed.

Chen Laoshi and his colleagues at the Affiliated Middle School of Zhejiang University, 1984

LRCCS: What do you mean by “what was really happening”?

Chen Laoshi: This is not a matter that can be covered in a few sentences. Many people on the top were saying one thing, but doing the exact opposite. They claimed that they were all about serving the people, but in fact they were after their own interests. For a minute example, back then, people like and above me had designated cars that drove them between home and work every day. But why should higher ranking employees be driven to work, when normal people had to walk? It didn’t seem fair to me. So I soon chose to bike to work. We were educated to serve the people since childhood, but the people who taught us that were privileged. How can people with privilege truly serve their people?

Later I had an opportunity to come to this university as a visiting scholar at the School of Education. I was here for about a year while my wife was kept in China for me to go back.

LRCCS: Which year was that?

Chen Laoshi: From 1987 to 1988.

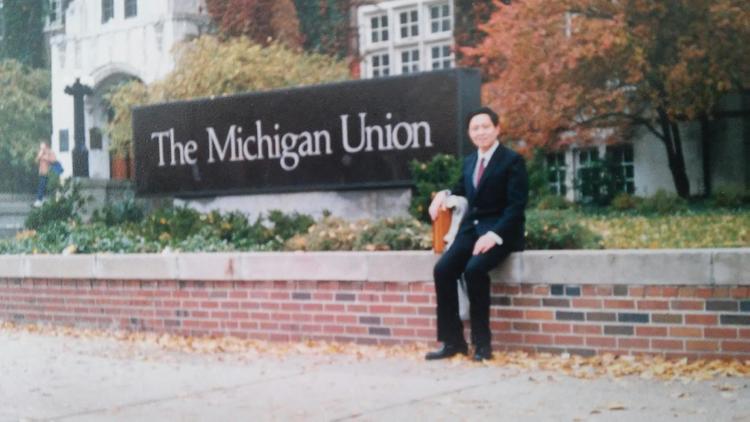

The first time Chen Laoshi visited the University of Michigan, 1987

LRCCS: What was your first impression of America?

Chen Laoshi: The whole environment, the whole society was totally different from China. During my first visit, I felt people in the U.S. were more relaxed, and smiled more often compared to Chinese. And you won’t get into trouble because of something you said.

After I went back from the States, a tragedy happened in China - the Tiananmen Square Protest in 1989. As a matter of fact, protests were seen in all major cities in China but without bloodshed. So during that time, students from my school were also protesting, hunger striking, and sitting on the railroad to block military transportation.

I was very unhappy during that time. First of all, policemen came to my school for investigations. They would always come to me. Fortunately enough, the policemen felt sympathy for students, too. They came to me and said: “President Chen, you can just say whatever you want to say. We only need something to report back to our superior.” There was another policeman who said: “We have no idea why on earth we are sent to colleges.”

However, the government was more terrifying than the police. People in my job were not allowed to go home at night. I had a temporary bed in my office. The Education Bureau could call me anytime, even in the middle of the night. They wanted to know where the students were, and what they were doing.

I visited my students when they were fasting on a public square. When I saw them, I could not say a single word. All I could do was hold their hands. I was deeply moved. Of course, you know what happened in Beijing later. In fact, there were also many things that happened in Hangzhou, and at our school that agonized me.

Two weeks after the Fourth of June, I quit my administrative job, and started considering leaving China. With the help of some professors at the UM School of Education, I got to come to America for a second time. At this time, I started to consider staying. And staying not just for living, but for making the largest contribution to society I could. For the first time, I got to choose what that would be - and I thought, I wanted to teach Chinese.

Around that time there still weren’t many Americans studying Chinese, but I knew that was about to change, and that was a big opportunity for me. I thought I could do three things. First, I could set up or improve a specific school’s Chinese language program. Later at UM I realized this wasn’t something I could do by myself - I needed all the teachers and all the classes to improve. The second thing was to create some kind of a breakthrough in one aspect of Chinese language study. So later I started to develop Business Chinese as an area of language study. With the support of UM, I started the Business Chinese Workshop (BCW) series, and in a ten year period held 4 national and international conferences. Perhaps UM and ALC didn’t think it was a big deal, but in the world of Chinese language education, it was quite important. The third thing was to make a contribution to the field of Chinese education in America. I joined the Chinese Language Teachers Association (CLTA), and felt responsible for improving the organization. Almost every year I attended the annual CLTA conference as a presenter or discussant or panel chair, and also published several articles in the CLTA scholarly journal. At one point I was on the CLTA board of directors. Aside from this, I worked with some colleagues in the publication of two important textbooks. I’ve also helped evaluate Chinese language programs and teachers in several higher education institutions.

LRCCS: You just mentioned there were three things you wanted to do when you came to America. But would you think they’re actually the same thing?

Chen Laoshi: You got it. These three things were indeed three aspects of one thing – Chinese language education. They were very clear in my head from the start. When I came to this country the second time in 1990, I was already 46 years old - I knew I didn’t have much time left in my career. But I decided that no matter what, I would accomplish these three goals. To make these goals happen, I decided to go to Brigham Young University (BYU) for a PhD program. This school was affiliated with the LDS Mormon church, so their language programs were exquisite. By the time I started school I was already 47. I thought I had much more experience than the younger peers, so I should also be a better student. So I put a lot of pressure on myself.

LRCCS: When did you first come to UM to teach Chinese?

Chen Laoshi: 1995, before I finished my dissertation at BYU. I was very excited, because this was my third time coming to UM and Ann Arbor. The previous two times when I left, I never thought I’d come back. But I did come back the third time -- as a faculty member. So if I believed in fate, I’d say it was my destiny to spend the second half of my life in Ann Arbor and UM.

LRCCS: How did you become so determined?

Chen Laoshi: When I was in China, all the work I did was never my choice. At that time, all we knew was to listen to the Party. If the party told you to do something, you did it. So you might say that people of my generation lost their sense of self. But after I came to America I finally had a chance to find myself. I could choose what to do for the second half of my life. And now I’m quite happy, because it seems like I’ve made the right choices. I chose to work with language education, I chose to go to BYU, I chose to teach at UM. I also chose to stay at UM. Most people don’t know this, but in 2001 I was offered a tenure-track position at the University of Virginia, but I eventually decided to stay at UM instead. And I’ve never regretted it. I’ve never forgot the three things I decided to do, and I’ve worked very hard to achieve them. But in 2013 when I received the Walton Lifetime Achievement award, the highest honor for Chinese education in the U.S., I was pretty surprised. This was because I’d never expected any kind of award, and this was also because only a few people had received this award.

LRCCS: What is the most important trait of being a good teacher?

Chen Laoshi: I think for a teacher, the most important thing isn’t his educational background, it isn’t his teaching experience, it’s not even his character or personality. What could be more important than those things? I believe it’s motivation, dedication, and the spirit of self-sacrifice. No matter how good your other things, if from the bottom of your heart you don’t love your work and your students, if you lack motivation and devotion, that’s just passing the time - you’ll never become a truly good teacher. You could also approach the question from another angle - it doesn’t matter if we’re talking about China or America, good students or not so good students. But if your students remember and miss you after the passage of decades, then you’re definitely a good teacher.

LRCCS: Thanks so much, Chen Laoshi. We’ve taken up much of your time, but our readers certainly appreciate it.

Chen Laoshi: Happy to have taken part. I hope your readers find my story useful.